Example For Belarus: Finland's Way To Join NATO

8- 20.05.2024, 18:02

- 16,098

Finns quickly changed their opinion about joining the alliance.

Charter97.org continues publishing articles from the book "Belarus in NATO", published by the European Belarus Foundation. This article was written by Professor Kari Liuhto from Finland.

As Finland’s road to NATO is considerably longer than our country’s actual NATO integration process, a brief summary of the history behind it is in order.

The Soviet Union failed to occupy Finland in World War II, and after the war, Finland was not part of the Soviet Union, unlike the Baltic States. Even though Finland was not occupied, it remained in the Soviet sphere of interest, which is why our country had to refuse, among other things, the Marshall Plan provided by the USA, due to pressure from the USSR.

The basis of relations between Finland and the Soviet Union was the Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance, or the YYA Treaty as we Finns call it. It also had a security policy dimension: the Soviet Union’s opportunity for military consultations if Finland had tried to break away from the Soviet sphere of interest. Particularly during the Hungarian Uprising in 1956 and the Prague Spring in 1968, Finland was concerned that social commotion in the Soviet Union’s Eastern European satellite states could trigger the Kremlin’s desire to start military consultations with Finland.

In addition to the YYA Treaty, the USSR sought to increase Finland’s dependence on the Soviet Union by, for instance, supporting the career development of pro-Soviet politicians in Finland and increasing Finland’s economic dependence on the Soviet Union. Since Finland was not a member of the socialist states’ Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON), the Soviet Union sought to increase Finland’s dependence by creating a clearing payment system five years after the Second World War. The clearing trade between Finland and the Soviet Union was based on the exchange of goods, with no need for convertible currencies, of which there was a chronic shortage in the USSR

The Soviet share in Finland’s foreign trade was at its highest at the time of the second international oil crisis in 1983, when the USSR accounted for a quarter of Finland’s foreign trade. The Soviet Union sought to increase Finland’s dependence, especially through its energy supply. Indeed, the Soviet Union accounted for a lion’s share of Finland’s energy imports.

For its part, Finland worked to prevent the Soviet goals from being achieved and Finland from falling under the control of the Kremlin. In 1956–1982, the President of Finland was Urho Kekkonen. He was a former employee of Etsivä keskuspoliisi, Finland’s secret police, and as the President, he took the management of the relations with the Soviet Union under his own control as well as defined that one of the main tasks of the secret police was to monitor and limit the spread of communism in Finland.

From the outside, it may have seemed that Finland underwent so-called Finlandisation and that Kekkonen could be steered by the Kremlin, but in reality, with close relations with the Kremlin, Kekkonen sought to edge Finland towards the West with the help of Nordic and European co-operation (a membership in the Nordic Council in 1955, an associate membership in the European Free Trade Association in 1960 and a full membership in 1985, and a free trade agreement with the European Economic Community in 1973) and by increasing Finland’s weight in the international arena, through the CSCE (Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe) process in the 1970s, for instance. Similarly, in order to prevent energy dependence from becoming too significant, Finland restricted the spread of natural gas as a household energy source and exported a significant part of Soviet crude oil after having refined it. Although Finland sought to curb the growth of the Soviet Union’s power to influence the country’s affairs, the USSR gained a fairly strong grip on Finland’s political and economic elite. However, the Soviet Union did not succeed in significantly influencing appointments in the Finnish Defence Forces and the secret police. An exception to the above is the Communist-led era in the secret police in 1945–1948. This so-called Red Valpo (Red State Police) was decommissioned at the beginning of 1949, and its successor was the current secret police, the Finnish Security and Intelligence Service (Suopo and later Supo).I

The situation changed dramatically in the early 1990s. The clearing trade between Finland and the Soviet Union ended unexpectedly at the end of 1990, and a year later, the USSR was dissolved. Without the dissolution, the Soviet Union would probably have continued to integrate Finland politically and economically into itself, and, for its part, Finland would have done its best to protect itself from the Kremlin’s embrace, which would have narrowed our independence. However, the dissolution of the USSR changed the situation. Russia’s watchful gaze waned and Finland moved to the West, where it has always belonged culturally and historically.

In 1992, the YYA Treaty was terminated in consensus by Finland and Russia. In the same year, Finland joined the newly established North Atlantic Cooperation Council (NACC). Another significant step was the purchase of equipment from the West by the Finnish Defence Forces, such as the decision in 1992 to buy F-18 Hornet fighter jets. Two years later, Finland signed a Partnership for Peace agreement with NATO. Finland joined the European Union in January 1995, at the same time as Austria and Sweden.

NATO co-operation was included in Finland’s foreign and security policy for the first time in the 1999 Government Programme. Several forms of NATO co-operation emerged: the Partnership for Peace, military exercise co-operation, crisis management operations, and the NATO compatibility of the Finnish Defence Forces.

In 2007, Finland’s option to apply for NATO membership was included in the Government Programme for the first time. This NATO option was also included in subsequent Government Programmes. Finland joined NATO’s rapid reaction force (the NATO Response Force) in 2008, and in 2014, Finland signed a host country agreement with NATO, the purpose of which is to facilitate practical co-operation between Finland and NATO.

Since 2015, Finland has participated in the NATO-led operation in Afghanistan, for instance. Even more importantly, the Finnish Defence Forces began to adjust its equipment and operating methods to be NATO-compatible. Without exaggeration, it can be said that even before Finland’s accession to NATO, the Finnish Defence Forces were more NATO-compatible than the armed forces of some countries that already were members of the alliance.

It may sound ironic, but it is an undeniable fact that Finland was ultimately taken into NATO not by our country’s political elite, but by the Russian President Vladimir Putin and the invasion he started in Ukraine in February 2022.

As a result of the invasion, the Finnish people became supporters of NATO membership “overnight”, and the Finnish Parliament turned almost unanimously to favour NATO membership. Before the invasion – more specifically in January 2022 – support for NATO among Finns was less than 30 percent, despite the war in Georgia in 2008 and the start of the war in Ukraine in spring 2014. The speed of the change is aptly illustrated by the fact that already in May 2022, three out of four Finns were in favour of NATO membership. In line with the principles of a functioning democracy, the Finnish President Sauli Niinistö took public opinion into account and started Finland’s NATO accession process.

Finland’s NATO accession process

17 May 2022: The President of the Republic of Finland decides, on the proposal of the Government, to notify the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) of Finland’s interest in engaging in talks on accession to NATO.

18 May 2022: Finland’s declaration of interest in acceding to NATO is delivered to the NATO Secretary General in a letter signed by the Minister for Foreign Affairs.

29 June 2022: NATO invites Finland to become a member in connection with the Madrid Summit.

4 July 2022: The President of the Republic decides to submit Finland’s letter of intent to NATO concerning its accession to the North Atlantic Treaty and its commitment to the obligations of NATO membership.

5 July 2022: All NATO member countries sign Finland’s Accession Protocol, and Finland becomes an observer member of NATO (invitee).

5 December 2022: The Finnish Government submitted a proposal on Finland’s accession to NATO to Parliament.

1 March 2023: Parliament approved the government proposal on Finland's accession to NATO.

23 March 2023: President of the Republic of Finland approved the accession and the bill for the Act to bring into force the NATO Accession Agreement.

30 March 2023: All NATO member countries have ratified the Accesion Protocol of Finland.

4 April 2023: Finland became a full member of NATO.

At the beginning of April 2023, a geopolitically significant moment in Finland’s history took place. Finland acceded to NATO, and thus Finland finally succeeded in detaching from the leash that Stalin had placed around the neck of the Maiden of Finland.

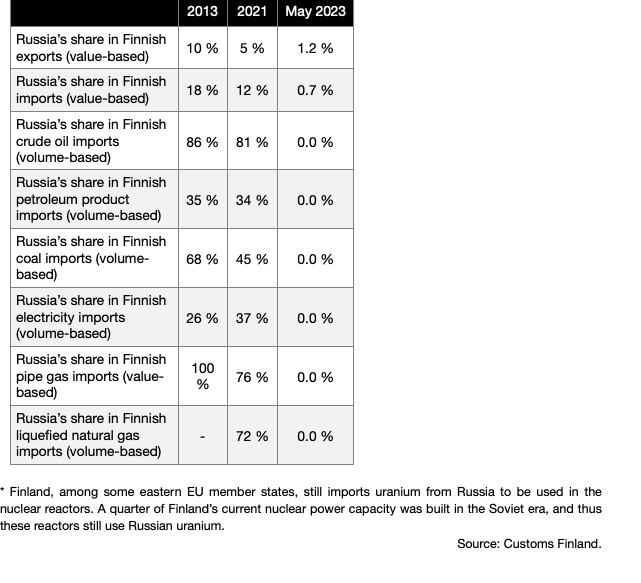

Finland’s NATO membership and the sanctions related to Russia’s invasion in Ukraine have had various consequences for Finland and its economy. Firstly, Russia’s share in Finland’s foreign trade collapsed. In May 2023, Russia accounted for only one percent of Finland’s foreign trade. Before the start of the war in Ukraine, the situation was different: in 2013, Russia accounted for just under 15 percent of our foreign trade.

Secondly, the Russian government took Fortum’s power assets in Russia under its control in the same month that Finland joined NATO. Before this nationalisation, the company accounted for at least three quarters of the total investment value of Finnish companies in Russia. At that time, the value of Fortum’s assets in Russia was EUR 5–10 billion, depending on the calculation method.

Thirdly, Russia has closed down the Finnish consulates in Petrozavodsk and Murmansk as well as its own consulate in Lappeenranta and has already decided to close down the Finnish Consulate General in St. Petersburg in October 2023.

In response, Finland plans to close down the Russian Consulate General in Turku in October 2023. It is also possible that Finland closes down the Russian Consulate in Mariehamn, Åland Islands, and perhaps even withdraws from the convention on Åland’s demilitarisation. It is also possible that in the future, foreign NATO troops will be permanently stationed on Finnish soil.

If Russia uses a nuclear weapon in Ukraine, either directly or via Belarus, Finland should acquire a nuclear weapon together with the other Nordic countries and the Baltic States or even alone. It should not be forgotten that NATO’s nuclear deterrent is largely based on US nuclear weapons. In addition to the United States, only France and the United Kingdom have their own nuclear weapons. When contemplating NATO’s nuclear deterrent, it should not be forgotten that there will be presidential elections in the United States in November 2024 and the former US President Donald Trump’s attitude towards NATO has been reluctant, at least in public. Another Republican politician, Ron DeSantis, has also stressed in his statements that the European NATO countries must take responsibility for Europe’s security. In his opinion, the United States should focus on curbing the growth of China’s influence.

Finland’s NATO membership undoubtedly increases the security of our country as our neighbour Russia is pursuing an aggressive foreign policy, and after Putin, Russia’s foreign policy may become even more intense. NATO’s common defence enhances Finland’s security but does not guarantee it. For this reason, Finland must continue to make additional investments in its military. In my opinion, NATO’s recommendation of using 2 percent of the country GDP for defence spending is not enough for Finland; instead, Finland should invest at least 3 percent of its GDP in defence.III In addition to additional financial contributions, general conscription, the comprehensive security concept and additional investments in internal security are essential for Finland’s defence and security.

I have worked researching Russia for more than 30 years, and I am delighted to say that Finland’s accession to the EU in 1995 and to NATO in 2023 are the most significant events during my career. Finland has finally fully joined the community of Western countries. However, this does not mean that the Russian threat is over, but we are now better prepared for the future. The eastern threat will only be over when the Kremlin realises how destructive its empire nostalgia is, both for itself and for its neighbours.

Lessons from Finland's NATO membership process for other countries aspiring to NATO: NATO membership was never an intrinsic value for Finland, but part of Finland’s separation from Russia’s sphere of influence and the completion of Finland’s western integration. This process has lasted throughout Finland’s independence, starting with the disarmament of the Russian troops on Finnish soil in 1918, continuing with the gradual joining of Western organizations that strengthen Finland’s status in international politics, and ending with Finland’s NATO membership in April 2023. Some valuable observations in Finland’s NATO membership process are the Western arms purchases, which ensured the compatibility of the Finnish Defense Forces with NATO even before the actual membership was realized. Another noteworthy point is that Finland advanced its NATO membership cautiously without causing a conflict with Russia. In my opinion, however, Finland should have joined NATO as early as 1999 with the countries of Eastern Central Europe, or at the latest in 2004, when the Baltic States joined NATO. Unfortunately, Finland’s then-leadership did not yet comprehend that Russia was on its way to an empire-nostalgic dictatorship.

The prerequisite for the security of Finland and the whole of Europe is democratic development in the neighborhood of the European Union. I hope the leaders of North Africa, the Middle East, Belarus and Russia understand the importance of democracy, because dictatorships are only quasi-sustainable states. All dictatorships fall sooner or later, causing instability and possibly even endangering the existence of these states.

I hope that I will still see someone at the head of Russia who values democracy and respects fundamental human rights, both in Russia and elsewhere. My hope may be futile but it is also necessary so that we Finns, too, do not see, and possibly also experience, turbulence caused by Russia in the future.

Notes

I. With the 2019 intelligence legislation, Supo became the security and intelligence service responsible for Finnish civilian intelligence. The Finnish Defence Forces have their own military intelligence unit.

II. By comparison, in 2022, Russia accounted for more than 60 percent of Belarus’s foreign trade, and the country’s energy supply relied almost entirely on energy coming from or through Russia.

III. In 2022, Russia officially spent more than 4 percent of its GDP on its military. In reality, the proportion is higher.

Kari Liuhto received his Ph.D. from the University of Glasgow, the United Kingdom, in 1997, and the degree of Doctor of Science from the Turku School of Economics, Finland, in 2000. Liuhto was nominated as a tenure professor in International Business at the Lappeenranta University of Technology in the year 2000, and he has been Director of the Pan-European Institute at the University of Turku since 2003 and Director of Centrum Balticum Foundation since 2011. Professor Liuhto has been involved in several projects funded by the European Commission and several Finnish ministries. Liuhto is the founder and the editor-in-chief of one of the world’s leading discussion platforms dealing with the Baltic Sea region, namely the Baltic Rim Economies (BRE) review, which has been published quarterly since the year 2004.